New Math? No Way!

“I’m 37 and I can’t do my third grader’s math homework.”

“My 13-year-old has left me in the dust in math – I have no clue what she’s doing.”

“My kid is crying, I’m crying…we surrender! He’s going to be a fourth grade dropout. This math is too hard!”

Sound familiar? In 2010, the Common Core State Standards Initiative was created to change how math was taught in American public schools, involving more understanding and less memorization. The goal was to improve America’s math scores, which lag behind many developed countries. The Federal Education Department is throwing different ideas around to see what will stick.

I am an educational therapist and work with kids who struggle to learn for all sorts of reasons. Dr. Olivia Miller, the older mom of a preteen, called me, very upset. Her son, 6th-grade Harrison, had been struggling in math since 3rd grade.

“Math was his favorite subject, but now he hates it! He used to make all A’s; now we’re lucky if he gets a passing grade. The worst part is, I can’t help him. I have a Ph.D. in Humanities, but this math makes me feel like an idiot.”

Calls like this are pretty common these days. Many students get bowled over by the mass of content their third and fourth grade teachers are trying to cover in math. The new “Common Core” math often means learning a multitude of strategies for every math function, some of which are unfamiliar even to the teachers.

She continued her story. “It started in 3rd grade. His dad had already taught him how to multiply. They loved working on it together. But when he went to school that fall, his teacher told him he was doing it wrong. He had to completely unlearn what he knew, and do it the new way. My husband was so aggravated! He couldn’t make any sense out of the worksheets Harrison brought home, and we watched our kid do worse and worse all year. The teacher tried to explain it to us, but it seemed like she barely understood it herself.”

She continued her story. “It started in 3rd grade. His dad had already taught him how to multiply. They loved working on it together. But when he went to school that fall, his teacher told him he was doing it wrong. He had to completely unlearn what he knew, and do it the new way. My husband was so aggravated! He couldn’t make any sense out of the worksheets Harrison brought home, and we watched our kid do worse and worse all year. The teacher tried to explain it to us, but it seemed like she barely understood it herself.”

The main thrust of the new methods, as you will see below, is to give children a better understanding of what is happening when you multiply numbers. Rather than just following an algorithm, most of the new methods are based around some form of taking numbers apart, doing “easy” math, then adding the answers back together. (More on that later. Don’t panic.)

When Harrison came to see me, he didn’t want to talk about math. In fact, he didn’t want to talk about anything. He stared at the floor, hands in his hoodie pocket. “He brought his laptop,” said his mom. “But he said he won’t do any homework with you. I hope he does. Try, okay, honey?” Her worried eyes skimmed over the slouched posture of her son. He mumbled something, and I encouraged her out the door. After meeting my three dogs and hearing about my own poor academic performance in middle school, he warmed up a little.

He explained: “I’m not bad at math, I’m really good at math, but I’m DOING terrible because my teacher hates me and also she’s really bad at explaining things. Nothing she says makes any sense. Look at this.” He opened his school laptop and showed me a hodgepodge of math grades, all the way from A to F. As I glanced over it, I noticed a bunch of zeroes, all unfinished assignments, which was very concerning. Understanding the steps in the process of doing math is crucial. If you miss the first steps, you probably won’t understand the later steps. “It’s too hard!” He slammed the laptop shut, our brief moment of camaraderie over.

“I’m really sorry you’ve had that experience. It sounds so frustrating.” I commiserated. “Can I see one of the assignments? I’m not the best at math. I’m curious if I can figure it out. Can I try?”

With addition and subtraction, the new math is not too different. Along with teaching the familiar strategy of stacking two numbers, and carrying if necessary, we also teach  children to base their thinking on 10. If you add 5 + 6, you picture splitting that number 6 into 5+1. So instead of 5 + 6, you have 5 + 5 + 1. When kids get used to it, this is a pretty easy way of adding numbers. Similarly, if you are adding 25 + 46, you first add the tens (20 + 40 = 60) then the ones (5 + 6 = 11), then add both of those results (60 + 11 = 71). This is easier for children to do in their heads than the old fashioned way. Being able to do mental math is a huge boost when learning harder math concepts, like division and fractions.

children to base their thinking on 10. If you add 5 + 6, you picture splitting that number 6 into 5+1. So instead of 5 + 6, you have 5 + 5 + 1. When kids get used to it, this is a pretty easy way of adding numbers. Similarly, if you are adding 25 + 46, you first add the tens (20 + 40 = 60) then the ones (5 + 6 = 11), then add both of those results (60 + 11 = 71). This is easier for children to do in their heads than the old fashioned way. Being able to do mental math is a huge boost when learning harder math concepts, like division and fractions.

When it comes to multiplication, it’s a different story. The new ways are quite different than the old ways. As Harrison and I sat there staring at his laptop, my stomach was awash with anxiety. This middle school math was based on the new math he hadn’t learned in 3rd-4th grade. I didn’t know it either! What if I couldn’t figure it out? While Harrison stared out the window, I took a quick peek at the new math rules. It started to make a little sense. I wrote the problem down on a piece of paper and got started. To my great relief, I was able to come up with an answer that I thought was correct. As I worked, Harrison’s arms uncrossed and his hands rested on the table as he watched me think hard. I pulled out my math-checking app and we discovered I got the right answer. We both smiled.

“Hey, I did it!” I was genuinely, goofily happy for myself, and he smiled too.

“Did you see how I did it?” I asked. “It wasn’t that bad.”

“I think so,” he said, “will you do another one?”

“Sure!” I said, a little more confident now. We checked each one as we went, me solving some, him solving some. We bonded over the math homework, and both ended the session feeling excited. Not as excited as his mom, who couldn’t believe we completed 3 missing homework assignments!

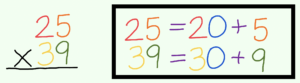

The new multiplication strategies are generally taught in third grade. Three of them are the same idea, with different presentations. In each of them, you start by breaking a number down into the “tens” and “ones.” For example:

36 is 30 + 6

72 is 70 + 2

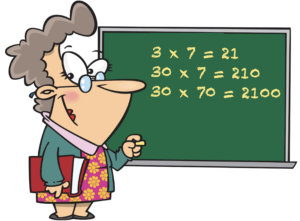

An early math lesson is that if you multiply a number with zero in the ones place, you can ignore the zero, do the multiplication, then put the zero back. So:

30 x 7 can be seen as 3 x 7.

3 x 7 = 21

Once you get the answer, 21, put the zero back, 210.

30 x 7 = 210

Even if both numbers have zeroes, this works.

Start with:

20 x 80

Change it to 2 x 8. Easy!

2 x 8 = 16

Then put all the zeroes back. This time, there are two zeroes, so we will put them both back. 1600.

2 x 8 = 16

20 x 80 = 1600

Those single digits are easier for us to multiply, and all of these math facts are easy and fun to learn with Online Times Alive! If you can do that, and you can separate a number into ones and tens, you can do all of the new math. I promise.

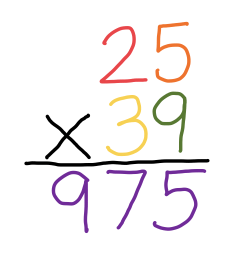

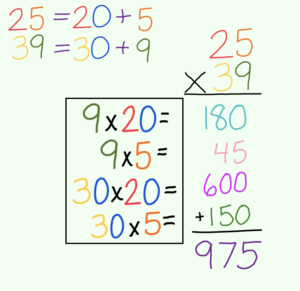

We will practice the strategies using two 2-digit numbers, 25 and 39. Remember how to divide them into tens and ones? Here are the methods and the steps.

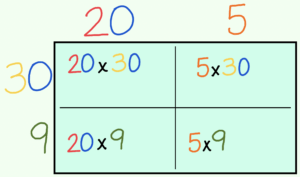

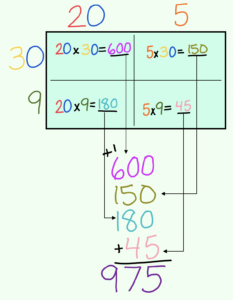

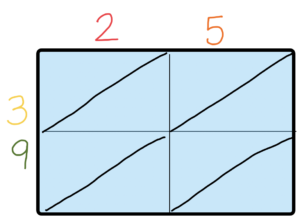

1. Box (Grid) Method

1. Draw a box, and divide it in half lengthwise and widthwise.

1. Draw a box, and divide it in half lengthwise and widthwise.

2. Break your two-digit numbers into tens and ones.  Put the tens and ones of the first number above your box. Put the tens and ones of the second number next to your box, as shown. →

Put the tens and ones of the first number above your box. Put the tens and ones of the second number next to your box, as shown. →

3. Use the boxes like a little chart. Multiply the top numbers by the side numbers.

3. Use the boxes like a little chart. Multiply the top numbers by the side numbers.

4. Write the answers in the boxes, then either use mental math, or write them down and add them up.

The next one should look familiar!

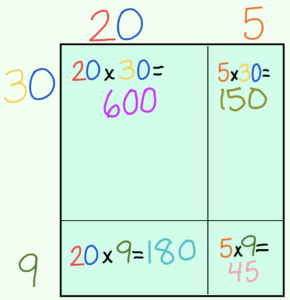

2. Area Method

This is EXACTLY the same as the Box/Grid method, except we’re changing how we draw the lines to  represent the size of the numbers. It’s not different in any other way.

represent the size of the numbers. It’s not different in any other way.

1. Draw a box, and divide it up both ways, but this time draw the “area” of the box representing the 20 much bigger than the area representing the 5. The area of the box showing 30 is bigger than the area showing 9.

2. Break the numbers into ones and tens and draw one set above the box, one set next to the box.

3. Just like the box method, use the boxes as a chart, and do the multiplication.

3. Just like the box method, use the boxes as a chart, and do the multiplication.

4. Add all four numbers and get the answer.

3. Partial Products

Again, this is basically the same method as above, we’re just going to skip the boxes and grids and go straight to the math. Sometimes, textbooks write this out in a somewhat confusing way, as below.

25 x 39

= (20 + 5) x (30 + 9)

= (20 x 30) + (20 x 9) + (5 x 30) + (5 x 9)

= 600 + 180 + 150 + 45

= 975

(Take a deep breath!) It’s really the same thing we just did in the Box Method, just without the Box.

Most people find it easier to see it this way.  In fact, many kids prefer this method to the standard, or algorithm, strategy we learned as children. Recognize all our math problems from the Box Method?

In fact, many kids prefer this method to the standard, or algorithm, strategy we learned as children. Recognize all our math problems from the Box Method?

⬅

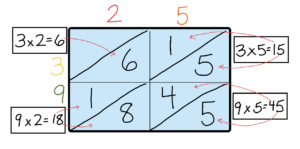

4. Lattice Method

Here is an interesting method that is new to the United States but is common in European countries. A lot of students really enjoy it. It feels kind of like a game to them. It is especially useful for kids who have trouble remembering details or holding numbers in their head to work with.

1. Once again, we draw a box, and divide it in half lengthwise and widthwise, creating four small boxes.

1. Once again, we draw a box, and divide it in half lengthwise and widthwise, creating four small boxes.

2. Something new: Draw 4 diagonal lines from the top right to the lower left corner of each of the four small boxes.

2. Something new: Draw 4 diagonal lines from the top right to the lower left corner of each of the four small boxes.

3. Write the digits of the numbers you are multiplying above and next to the box. No breaking up of tens and ones; just write the numbers. That’s one of the things that makes this method different.

3. Write the digits of the numbers you are multiplying above and next to the box. No breaking up of tens and ones; just write the numbers. That’s one of the things that makes this method different.

4. Multiply the numbers on top by the numbers on the sides. Write the answers in the small boxes, just like we did before.

4. Multiply the numbers on top by the numbers on the sides. Write the answers in the small boxes, just like we did before.

5. This time, write the tens digit above the diagonal line, and the ones digit below it. When you multiply 2 x 9 = 18, write the 1 above the slanted line, and the 8 below it. If there is nothing in the tens place, you can  leave it blank or write a zero.

leave it blank or write a zero.

6. Can you spot the long diagonal lines you created when you first drew the short slanted lines? It divided the box into long, diagonal sections. We’re going to add up the numbers in each section, as you can see below, then put them together for the answer.

Because this one is a bit challenging to understand (although it’s one of the easiest to do, and for that reason many kids love it), here’s one more example, using different numbers.

Any one of these methods might be the best for your child. Kids who love math usually prefer Partial Products. Visual learners prefer the Area Method. Kids who struggle with math enjoy the Lattice Method, as it involves only single digit multiplication, which you can master with Online Times Alive! For those of us who like the Old-Fashioned way, it still works very well. If your child struggles with that one, try adding a turtle head:

Any one of these methods might be the best for your child. Kids who love math usually prefer Partial Products. Visual learners prefer the Area Method. Kids who struggle with math enjoy the Lattice Method, as it involves only single digit multiplication, which you can master with Online Times Alive! For those of us who like the Old-Fashioned way, it still works very well. If your child struggles with that one, try adding a turtle head:

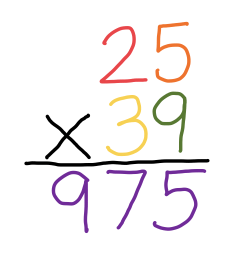

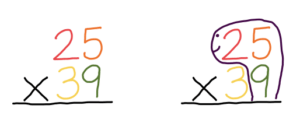

5. Standard Algorithm (The Old-Fashioned Way, With a Twist)

1. Draw a turtle head around the problem.

1. Draw a turtle head around the problem.

2. Multiply by the neck number.

2. Multiply by the neck number.

3. Cross out any carried numbers, draw a collar on the turtle, and lay an egg.

3. Cross out any carried numbers, draw a collar on the turtle, and lay an egg.

4. Multiply by the next number. Add.

This still works well, and most kids, once they learn it, stick to it. Less writing and drawing and adding and figuring.  In case you’re wondering, test scores have NOT risen since we introduced new math in 2010. This could be because there is not much buy-in from the community; adults, including teachers, do not want to learn new way to do math. Another possible reason is because, unfortunately, in many of the new textbooks, they are including all of these ways to do multiplication and division. The teachers, hurried by impending tests, administrative checklists, and anxious post-pandemic parents, go through the methods as quickly as they can. Often children don’t get a complete understanding of any of them and end up more confused than ever. Hopefully we’ll switch to teaching one or two strategies, and let the kids do the research if they want something else!

In case you’re wondering, test scores have NOT risen since we introduced new math in 2010. This could be because there is not much buy-in from the community; adults, including teachers, do not want to learn new way to do math. Another possible reason is because, unfortunately, in many of the new textbooks, they are including all of these ways to do multiplication and division. The teachers, hurried by impending tests, administrative checklists, and anxious post-pandemic parents, go through the methods as quickly as they can. Often children don’t get a complete understanding of any of them and end up more confused than ever. Hopefully we’ll switch to teaching one or two strategies, and let the kids do the research if they want something else!

Harrison is in 8th grade now. Math is much less challenging for him, although that year was a struggle for both of us. New concepts are confusing for adults as well as children, but that doesn’t mean they don’t work.

6. Get a Membership — Online Times Alive to learn all the times tables.

Be patient with yourself and your child, and use Online Times Alive to make all those math facts easy. Once you’ve mastered your facts, any of these methods will work! Online Times Alive uses songs and animated stories to teach the facts 0s-9s. When students learn the story, they remember the outcome of the story and that is the answer. Online Times Alive keeps track of individual progress with scores and lessons completed.

This Blog Post is by Amy Richter

After a childhood of school struggles, Amy Richter became a teacher at age 21. Following decades of classroom teaching, she opened ChildFirst Learning and became an Educational Therapist, working exclusively with children who have difficulties in school. Kids know her for unswerving devotion to their happiness and education, as well as games, fun, and laughter. Her teaching is based on research and evidence-based practices, using new tools and solutions to age-old problems. Her goal is to share this knowledge so that kids love learning, enjoy school, and continue their education on their own.

After a childhood of school struggles, Amy Richter became a teacher at age 21. Following decades of classroom teaching, she opened ChildFirst Learning and became an Educational Therapist, working exclusively with children who have difficulties in school. Kids know her for unswerving devotion to their happiness and education, as well as games, fun, and laughter. Her teaching is based on research and evidence-based practices, using new tools and solutions to age-old problems. Her goal is to share this knowledge so that kids love learning, enjoy school, and continue their education on their own.

Leave A Comment