Ten Tips for Kids Who Struggle with Writing

Dealing with Dysgraphia

“Everybody pull out of a piece of paper, please, and write your name at the top.” It’s time for dictation. I use words from my 3rd-4th graders’ weekly spelling assignment in silly or dramatic sentences, then have the children proofread each others’ work.

“Number one,” I begin, after reviewing the instructions, “my fiendish friend will hand me the sandwich. My fiendish friend will hand me the sandwich.” I repeat it several times as my eyes rove around the room, checking everyone’s progress. Suddenly I realize that my new transfer student, André, has nothing on his desk. He is sitting quietly, with a slightly anxious face and empty hands. As the children’s pencils scratch their way across their papers, I quickly and quietly move across the room and kneel by his desk.

“André, where is your paper?”

“What paper?” His eyebrows crease and he gives me a hopeful little smile.

I go through the instructions again while looking into André’s soft brown eyes.“Take out a lined piece of paper. Put your name at the top, and then write the number one on the first line. Then, when I say a sentence, you write it down. I’ll say the sentence as many times as you need me to, okay?” He seems to both hear and understand, and pulls out paper and pencil.

“You can just start with number two, okay? Don’t worry about the first one.” His doe-like eyes just look at me, full of trepidation. By now half the class is looking our way.

“Okay, class. Number two.” I quickly revamp the sentence I was going to say, and switch to a simpler one. ‘The cat is smart, silly, and nice.’” To  my consternation, André continues to gaze around the room. I kneel again. “André,” I whisper, “take your pencil and write down the words I just said. The cat…” He picks up his pencil and laboriously begins to write. As I repeat the sentence a few times, I watch as he marks in a wild jumble of upper and lower case letters, “THCzsMTsLENdniS.” My heart sinks as his worried eyes dart up to look at my face. “There you go,” I offer, “you wrote it. That’s just what to do.” By now, we have the entire class’s attention on our mini-drama, so I stand up to catch my co-teacher’s eye, and she walks over. Mary’s eyes widen as she looks at what André has written, and without speaking, she kneels by his desk. As I move around the room, finishing the dictation exercise, I hear her softly encouraging him. I quickly decide to skip proofreading and let the kids out a few minutes early. During recess I review Andre’s transcripts and see that he has passed kindergarten, 1st, 2nd and 3rd grade. There are some bland, uninformative comments from his previous teachers. No mention of any difficulties in any subject.

my consternation, André continues to gaze around the room. I kneel again. “André,” I whisper, “take your pencil and write down the words I just said. The cat…” He picks up his pencil and laboriously begins to write. As I repeat the sentence a few times, I watch as he marks in a wild jumble of upper and lower case letters, “THCzsMTsLENdniS.” My heart sinks as his worried eyes dart up to look at my face. “There you go,” I offer, “you wrote it. That’s just what to do.” By now, we have the entire class’s attention on our mini-drama, so I stand up to catch my co-teacher’s eye, and she walks over. Mary’s eyes widen as she looks at what André has written, and without speaking, she kneels by his desk. As I move around the room, finishing the dictation exercise, I hear her softly encouraging him. I quickly decide to skip proofreading and let the kids out a few minutes early. During recess I review Andre’s transcripts and see that he has passed kindergarten, 1st, 2nd and 3rd grade. There are some bland, uninformative comments from his previous teachers. No mention of any difficulties in any subject.

Hallmarks of Writing Disorders

I will come to find, though, throughout this school year, that André cannot write in sentences and has intense difficulties with processing and organizing information, whether he is answering questions or trying to complete his own ideas on paper. He is sweet; so humble and easygoing that I’m sure whichever overburdened, overworked teacher had him before was just grateful that he never caused any trouble. Now, in a smaller setting, it is clear, even without testing, that André ticks off most of the boxes on both the dysgraphia and written expression disorder checklists, including:

I will come to find, though, throughout this school year, that André cannot write in sentences and has intense difficulties with processing and organizing information, whether he is answering questions or trying to complete his own ideas on paper. He is sweet; so humble and easygoing that I’m sure whichever overburdened, overworked teacher had him before was just grateful that he never caused any trouble. Now, in a smaller setting, it is clear, even without testing, that André ticks off most of the boxes on both the dysgraphia and written expression disorder checklists, including:

- messy handwriting

- trouble expressing thoughts in writing (whether typing or by hand)

- slow and/or painful writing

- trouble with grammar, punctuation, and word spacing

- skipped letters when writing words

- issues with automaticity (having tasks become automatic, as in times tables or letter formation)

- difficulties when planning writing, even when using graphic organizers or other tools

Ten Tips for School Success

There is not yet any scientifically proven method of “curing” dysgraphia or OWL (oral and written language learning disability), but there are many things you can do to support your child’s learning.

- Testing – Find a pediatric neurologist, school psychologist, or educational therapist who can assess your child. They can help you get a 504 plan or even an IEP (Individualized Education Program) that will put accommodations in place to make school more manageable.

- Assistive Technology – You can dictate into Google Docs, make editable PDF’s out of paperwork, and even adapt math worksheets, using a program like KiWiWrite.

- Oral Answers – Get an assistant, a helpful parent, a volunteer, or another student to write down a student’s answers during the school day. If it’s a short question, for example the “Why” that is often tacked onto a math word problem, see if the child can give their answer verbally.

- Typing – Most adults with dysgraphia remember the moment when typing completely changed their lives. Typing.com is a great online resource for teaching kids to type.

- Graph Paper for Math – provide your child with 1 cm graph paper for all math operations, but especially in 3rd+ grade, when they start multiple digit multiplication and long division.

- Information – Share links to great websites like Understood.com and ADDitudemag.com to anyone who will be requiring your student to write.

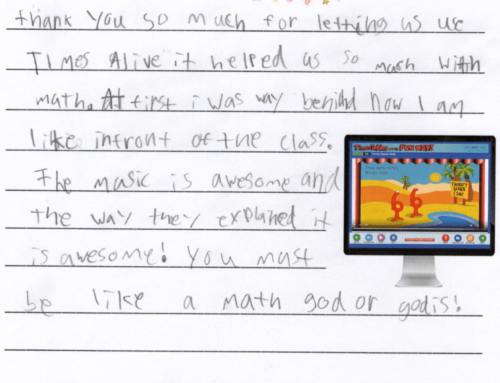

- Alternate Methods – find alternate methods to teach automatic tasks. Use resources like Online Times Alive from CityCreek.com to teach multiplication using songs and stories to jog the memory.Try it for free here: Online Times Alive

- Copying – provide writing examples for them to copy or trace, emphasizing letter direction, word spacing, and punctuation. Even with typing, texting, and dictating, it is still important to be able to write simple sentences on cards, notes, and forms.

- Change the Task – Can the child number the words in a word list rather than rewrite them and “fill in the blank?” Is there a multiple choice version of a test? Can the teacher assess their spelling ability without having it affect their grade? Getting low grades does not motivate these children — it just increases their anxiety about something that is out of their control.

- Find the Fun – Provide fun and creative opportunities for your child to work on story organization. Take turns tell

ing a story with them, word by word or sentence by sentence. Create comic books where they draw the pictures and you write the words.

ing a story with them, word by word or sentence by sentence. Create comic books where they draw the pictures and you write the words.

Accept that dysgraphia is real. Children’s hands and arms tire and hurt. Even when they are trying as hard as they can, their words may come out misspelled or out of order. They may never be fluent at handwriting, but they can learn to not dread writing assignments if you accept their limitations and celebrate their strengths. André is now a thriving ninth grader, proficient at using dictation technology and hoping to someday be an architect.

This Blog Post is by Amy Richter

After a childhood of school struggles, Amy Richter became a teacher at age 21. Following decades of classroom teaching, she opened ChildFirst Learning and became an Educational Therapist, working exclusively with children who have difficulties in school. Kids know her for unswerving devotion to their happiness and education, as well as games, fun, and laughter. Her teaching is based on research and evidence-based practices, using new tools and solutions to age-old problems. Her goal is to share this knowledge so that kids love learning, enjoy school, and continue their education on their own.

Leave A Comment